Typically, in the international arena, the improvement of relations between two adversarial parties begin with technical meetings at the intelligence and military levels to first discuss the details, followed by meetings between foreign ministers and then, finally, heads of state to finalize the whole process.

While Turkiye and Syria have already had technical discussions at the meeting that included their defense ministers and the intelligence chiefs of Turkiye, Syria, and Russia in Moscow on December 28, 2022, the final steps may become clear after the meeting, expected in early February, of the two countries’ foreign ministers. That meeting will confirm how serious Ankara is in restoring relations with Damascus at all levels after such relations were severed for years.

The day after Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar met with his Syrian and Russian counterparts, he stated that his country’s goal of rapprochement with Damascus is to preserve Syria’s unity. He emphasized that the participation of all parties in ensuring Syria’s stability will be in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 2254.

With these statements, it is clear that Ankara’s strategic goals to restore relations with Damascus stem from its desire to ensure that a separatist Kurdish entity will neither exist nor expand its influence under American auspices. What also becomes clear is providing a suitable ground for the Syrian refugees return within an atmosphere that guarantees Resolution 2254 implementation, according to the Russian interpretation, that is based on the formation of a national unity government—not according to the principle of establishing a transitional rule phase, as the latter principle has become contrary to the conditions of reality.

In this context, there was a positive interaction on the part of Syria, which found common interest with Moscow and Ankara in the issue of forming a quadripartite framework—Syria, Russia, Turkiye, and Iran—that agrees on the point of confronting any separatist or federal entity in northern Syria.

This paper seeks to estimate the transformations in northern Syria by answering the following questions.

What are the changes that will take place to the military movements in Idlib and the areas of Turkish influence in northern Syria?

What is the nature of the changes to the influence of the Kurdish movements in northeast Syria?

What are the main challenges that could face the trilateral track between Ankara, Moscow, and Damascus in northern Syria?

The "Strategic Decisiveness" of the Scene in Northern Syria

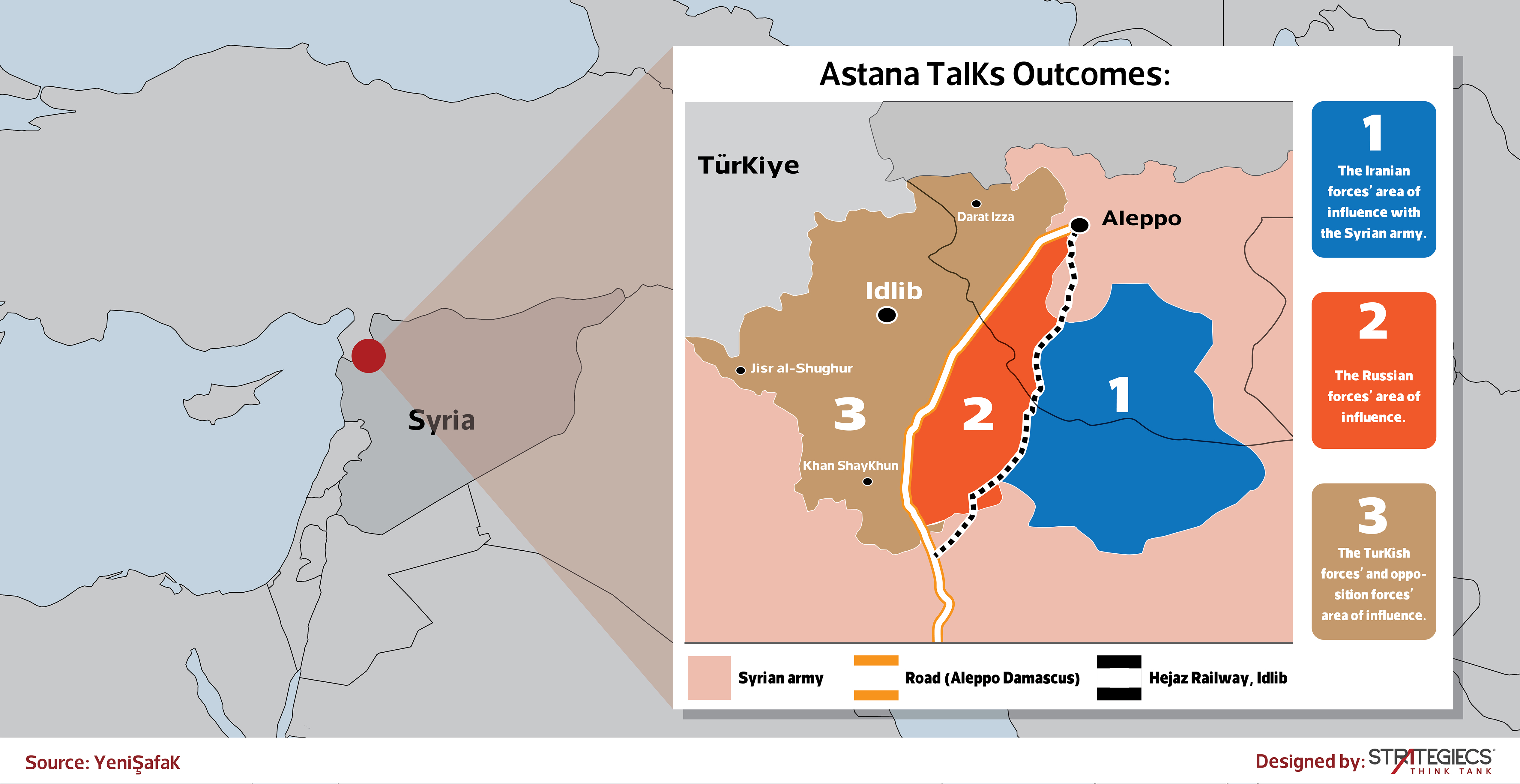

The centers of power distribution and influence in the Idlib governorate and its surroundings is governed by the formula of the interim solution reached by the Astana parties in September 2017, which divides Idlib as follows:

- The control of the Syrian army extends to the east of the Hejaz-Aleppo railway.

- The areas of Russian influence extend from the Hejaz-Aleppo railway to the Aleppo-Damascus highway.

- The areas of Turkish influence and the presence of armed groups supported by Ankara extend from the Aleppo-Damascus highway to the Turkish border. Turkiye, in northern Syria, also has about 118 military sites distributed over Latakia, Idlib, Afrin, the Euphrates Shield area, and the Peace Spring area.

While the agreement of the Astana parties included getting rid of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (formerly Jabhat al-Nusra), a former al-Qaeda affiliate and UN-designated terror organization that controls parts of Idlib and Afrin, and imposing civilian rule via what it calls the “Salvation Government” through fighting or floating. Ankara ensures that the armed opposition groups it supports, specifically the so-called Syrian National Army, would not launch attacks against the Syrian army. The Syrian National Army is located in the Euphrates Shield areas north of Aleppo and in the Peace Spring area, which includes parts of northern Aleppo, Hasaka, Raqqa, and Afrin. The Astana parties are to follow the course of talks to reach a final formula for a solution that guarantees the interests of all.

However, Syria, with Russian support, later sought to surpass interim solutions and bypass the Astana understandings with a new attempt to achieve a strategic decisiveness in the map of northern Syria while maintaining direct coordination between the three parties of influence in the Idlib governorate. This quest became apparent after Syrian forces regained areas in southern Idlib, including Maarat al-Numan in 2020, contrary to Ankara’s wishes at the time.

Moreover, the United States insisted on relying on the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces in the fight against ISIS. Turkiye saw such insistence as a threat to its national security, added to the economic and political pressures resulting from the Syrian refugee file and the impact it has on popular trends in the upcoming elections. Ankara, therefore, shifted more towards consensus on the issue of strategic decisiveness.

Geopolitical Situation Scenarios in Northern Syria

First scenario: Cypriot version

This scenario, circulated in the media, simulates direct Turkish control of Northern Cyprus in 1974. The Turkish army was deployed in the areas of Turkish population density in Northern Cyprus based on the 1959 London Agreement, which gives Britain, Turkiye, and Greece the right to a military guarantee of peace in the island.

In the same context, it is claimed that Turkiye has the right of guarantee in northern Syria, in accordance with the agreements signed on the sidelines of the Astana talks. Therefore, Turkey will be deploying its army in the entire north of Syria while the Russian forces will form a dividing line that prevents clashes with the Syrian army, preventing these two forces from advancing towards Turkiye and the Syrian armed opposition groups’ areas of influence, which will become, geographically and militarily, independent from Damascus but without political independence at the international level.

This scenario is contrary to reality, and remains unlikely due to the following six factors:

- The presence of several active international actors in Syria, including Russia and Iran, strongly oppose this scenario since it establishes the geographical division of Syria. They have periodically demonstrated their objection by targeting Turkish areas of influence both on the ground and in the air. Also, there is no American inclination to implement this scenario, which perpetuate conflicts, either directly or through proxy groups, targeting Turkish areas east of the Euphrates. This deprives Turkiye of the legal justification to execute the scenario.

- Ankara is aware that this scenario is not strategically feasible since it lacks a legal basis for Turkiye to implement it. The legal document in force for Ankara’s intervention in Syria is the 1998 Adana Agreement that grants Turkiye the right to intervene—temporarily and not permanently—within a distance of 5 kilometers. The Astana talks also did not give Ankara the right to extend its influence in the northern regions strategically; rather, it gave Ankara the right to an interim guarantee to consider the mechanism for resolving a strategic settlement in accordance with the quadripartite framework of Turkiye, Syria, Russia, and Iran.

- There is Arab and regional resistance to Turkiye’s growing influence in the Arab region. This competing influence ultimately affects the balance of power, which is likely to be in Turkiye’s favor at the expense of other Arab and regional countries.

- The enormous economic and human cost incurred by in hosting nearly 5 million Syrians in its areas of influence is significant, especially since these areas lack sufficient economic resources to provide an adequate income.

- Ankara has no domestic popular support for a permanent deployment in Syria. There is political objection to and popular discontent with the military deployment there that sometimes results in casualties for the Turkish army.

- The nature of the Turkish goal in northern Syria to confront the Kurdish separatist movements’ expansion of influence. Turkiye would favour a low-cost solution—if any—that topples the influence of such movements.

Second scenario: Chechenizing and Turkiye’s preservation of functional spikes

“Chechenizing” is a term that refers to the process of resolving the Chechen crisis in 1999. Moscow tended to resolve it by dividing the Chechen fighting factions into those that reconciled with Russia and those that remained its enemy. The latter factions were exterminated by the reconciled factions. Then the reconciled factions were accommodated within the framework of a political or military entity controlled by the central entity.

With this mechanism, Moscow was able to divide the factions of northern Syria at the beginning of the Astana talks. Turkish support of Moscow was signalled by inviting some “moderate” factions to the Astana talks, whereas radical factions, such as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), were neutralized.

What is complicating the scene, however, is that small militant factions have been divided, such as Jund al-Aqsa, and large factions, such as HTS, have faced defections to smaller but more radical factions, such as Hurras al-Din.

The second phase of the applying this scenario includes the following points:

- The integration of armed Syrian opposition factions under a military coalition ensures Turkiye maintains a functional tool that can be mobilized according to its interests when needed.

- Exterminating the armed factions or the currents that reject a political solution through targeting them and arresting their members. Ankara practiced the same against Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham when HTS tried to control all areas of Afrin. In the same context, Moscow will not hesitate to target armed factions. The extremist factions will end up in the scenario al-Qaeda did in Afghanistan after 2001: taking refuge in remote areas.

Called the “Tora Bora” scenario, al-Qaeda fortified itself in the mountains of the Tora Bora region. Likewise, militants in Idlib will end up taking refuge in some remote areas. In this context, moderate militants can be absorbed within HTS and a clash can take place with the extremist militants to be expelled from vital areas, fighting them in remote areas via international actors in Idlib.

- The withdrawal of the Turkish army while maintaining some of Turkiye’s military points in the Syrian territories up to 30 kilometers. These points are a guarantor of a solution at the strategic level in case any of the parties may seek to violate the agreement. This was applied in the areas controlled by the Syrian army up to Maarat al-Numan, which Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu hinted Turkiye would withdrawal from in exchange for a political solution that ensures stability.

- Transforming the areas controlled by the moderates into local administrative councils under a “Council of Regions.” It would bring together the Damascus government and figures affiliated with the political opposition within a framework that more closely resembles federalism. This was previously included by Moscow in the constitution version that it presented.

Levers to implement this scenario include:

- Turkish statements and hints about its readiness for a gradual withdrawal from Idlib, provided that an agreement is concluded giving it the right to intervene in Syrian territory for a distance of 30 kilometerss, along with installing Turkish bases that guarantee the solution at a strategic level. There is an insistence on this point, which Moscow supports, to achieve a strategic settlement on a win-win approach. That is, a solution that is in the interest of both parties.

- The Russian desire to keep the Turkish side active, even relatively, in Syria as a balancing element regarding Iran as well as the United States, whose moves contradict Ankara’s ambition.

- There is a high chance of success in integrating armed factions. For example, Fateh al-Sham was able in 2017 to merge with four fighting factions, as a result of which HTS was formed.

- The decrease of funding sources for these factions coupled with the cessation of relief associations work in northern Syria (with the exception of Turkish associations) is an economic factor that pushes the factions and people in northern Syria to accept the path of a solution.

- Moscow’s hint of accept the “Chechenizing” formula by proposing a constitution that does not object to establishing local councils with a political and military character under the umbrella of the single political control of the Damascus government.

- The existence of an actual participatory Russian-Turkish deploy in the form of an international guarantor of the solution.

- There is a sort of Arab acceptance of this track as an alternative to the scenario of direct Turkish military presence. The Arab countries want to raise the level of accepting the Syrian regime at the international level to give their relations with it a state of legitimacy.

Looming challenges

First, Iran’s attempt to obstruct the settlement by motivating the armed groups it supports and supporting the Syrian army to target areas under Turkish control. This challenge was not fruitful when Tehran adopted it in previous years because Ankara was able to aggressively defend its influence.

Second, Russian prevarication prevents Ankara from achieving everything it seeks, specifically with regards to the number of the Turkish military bases and soldiers that will maintain their deployment inside Syria. Moscow, meanwhile, calls to classify all Syrian armed groups as terrorists.

Third, HTS’s rejection to the reconciliation. However, by applying the “Chechenizing” scenario or the “Tora Bora” scenario, HTS’s intransigence may be brought to an end. In addition, the pragmatic personality of HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Julani needs to be taken into consideration. He showed his awareness of the facts in Idlib, and his inability to deviate from the regional and international context are factors that ensure the elimination of this challenge.

The Geopolitical Situation Scenarios in Northeastern Syria

The scenarios, in the case of northern Syria, specifically the city of Idlib and its surroundings, do not apply to the geopolitical situation in the northeast, where the U.S.-Russian compete, in addition to the presence of Kurdish movements represented by the forces of the Democratic Union Party and some of its allied parties in the areas of Tal Rifaat and Manbij.

In Tal Rifaat, the Kurdish Protection Units (YPG), the military wing of the Washington-backed Democratic Union Party (PYD), control those areas. Moscow sometimes plays a counterbalancing role in the context of the U.S.-Turkiye dispute, while at the same time strengthening Russian influence there, with the negotiating cards Moscow has against Ankara regarding Idlib city. There are also the Russian-Kurdish relations, with Russian air cover contributing to the YPG’s takeover of the city of Tal Rifaat in February 2016. Since it is geographically separate from the eastern Euphrates region, the city of Idlib is not in the sphere of interests for either the United States or the Kurdish Autonomous Administration.

In Manbij, the region is governed by U.S.-Russian convergences based on the desire of the two countries to prevent the expansion of Turkish influence in the Syrian north. The forces of these two countries, in addition to the presence of the Syrian army, were deployed in the vicinity of Manbij since 2018.

Washington views its presence as a strategic matter for the two main parties, whether Republican or Democratic, as this influence was established under Democratic President Barack Obama, continued under Republican President Donald Trump, and is maintained by Democratic President Joe Biden. Through its presence, Washington seeks to achieve a participatory international-regional spread that balances Russian and Iranian influence within the strategy of containment and encirclement.

The strategic solution in the areas east of the Euphrates requires broader Russian-American understandings in parallel with separate Turkish-American understandings This complicates the scene in the northeastern Syrian regions. However, there are several objective factors that appear in Washington’s face to implement the same scenario, that Ankara seeks in Idlib and its surroundings, a scenario of legitimizing its military deployment while maintaining military forces within allied local councils, which will include Kurdish forces with some Arab forces, such as the Syrian Elite Forces and other tribal forces.

This scenario includes granting the areas east of the Euphrates a limited administrative, security, and cultural autonomy while keeping them politically connected with Damascus. For example, there would be a relative Syrian military deployment in these areas, which is already there.

Realistic factors and indicators of this scenario:

- Washington controls the reconstruction process through laws of an international nature, such as the Caesar Act and the Captagon Act, which gives Washington great influence, especially since it is estimated that the cost of reconstruction is $ 250 billion, which cannot be provided by any country or international financial institutions without Washington’s permission.

- The Caesar Act stipulates that “the application of the law can be gradually suspended if the parties to the conflict engage in meaningful negotiations.” Meaningful negotiations are in the American interest.

- Ankara’s awareness of the difficulty of confronting American influence in this region, besides its desire to diversify the balance of power east of the Euphrates between Moscow and Washington.

- Washington’s establishment of local government councils in this region.

- Seeking to surround the administration system there with an Arab-Kurdish demographic mixture to deepen its influence on a popular level.

In conclusion, floating the armed factions within an integrated military wing or corps— via a military presence of the Syrian army forces in Idlib and northern Aleppo, and via a joint Russian-Turkish guarantee, provided that Ankara remains under its political and security influence—is the most likely scenario supported by several factors and by realistic indicators. Most notably is the existence of a relative Turkish-Russian consensus in return for the control of Tal Rifaat to the Syrian regime and the exit of Kurdish Protection Units therefrom. As for the northeast of Euphrates, control there remains with the U.S.-backed Kurdish movements.

The course of the expected solution in Syria is similar to what happened after the War of the Spanish Succession broke out due to the lack of an heir to King Charles II of England. The 1714 Treaty of Rastatt concluded between France and Austria divided influence in Spain politically but not geographically—a sharing of influence that preserved the balance of power between the conflicting actors.

* The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author. Strategiecs shall bear no responsibility for the views and/or opinion of its author on security, economic, social, and other issues, as they do not necessarily represent the views of the Think Tank.

Keep in touch

In-depth analyses delivered weekly.

Related Analyses: