Man sanctifies what he considers as his salvation, a fact proven by history. It also applies to groups that work, consciously or unconsciously, to expand the aura of sanctification and to impart features of the “savior” that may not exist. Thus, they build their dreams on an illusion from which they soon are awakened. holding it accountable for their disappointments and setbacks while forgetting that they were the ones who built this ladder of illusion on which they pinned their highest hopes before its inevitable collapse.

The right status would have been a “life ladder” or pillar that becomes more firmly established over time. To a significant extent, this image applies to Arab nationalism, which was the slogan of a sensitive and fateful stage in our modern history as a nation.

The term nationalism did not appear widely before the end of the nineteenth century, as it was not an influential factor in political behavior. Rather it was closer to “social imagination that has become realistic tools,” as defined by the English historian Benedict Anderson. This term took its initial form during the American and French Revolutions. However, the results of these two revolutions did not provoke the Arabs until the late nineteenth century when nationalism appeared to revive the Arab bonds between them and weave the future of their country from its durable threads.

So, what happened? Why did these threads fray and cut so many in the Middle East? Fragmentation, discrimination, extremism, escalating narrow loyalties, and dependence on the external is the resulting devastation that we Arabs have been harvesting for decades.

The term Arab nationalism had, during the first decades of the last century and what followed, its weight and impact that was responsible for tickling the feelings of masses extending from the ocean to the Gulf, as if it were a common spirit that unites them, or the absolute spirit as German philosopher Hegel calls it; a spirit that settled in a grieving body stricken under long decades of tyranny and occupation.

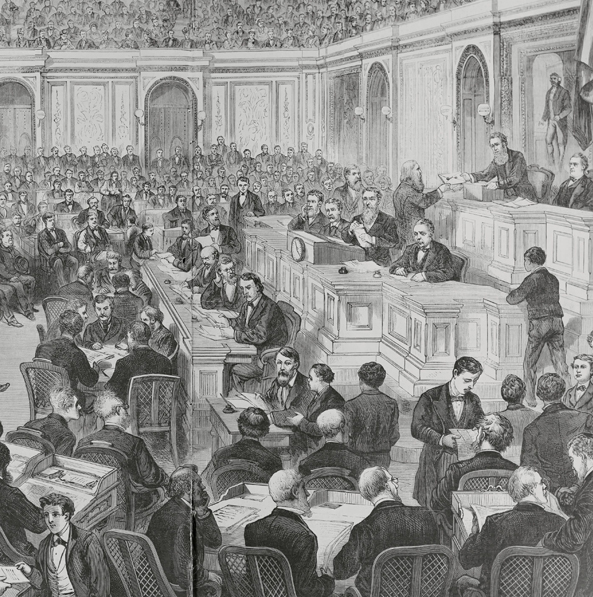

The Arab nationalist movement began to crystallize at first by writers such as Nasif al-Yaziji and Boutros Al-Bustani, who relied on the Arabic language to revive and revitalize the national spirit. The Syrian Scientific Society (1857) and Beirut Secret Society (1875) called for the establishment of an independent unified state in Syria and Lebanon on nationalist bases, followed by the Association of the League of the Arab World (Ligue de la Patrie arabe) founded by Naguib Azoury in Paris in 1904. Then thinker Abdul Rahman al-Kawakibi carried the call for nationalism and demanded the return of the caliphate, the Arabs who make up the heart of Islam.

Al-Fatat or the Young Arab Society was one of the most important associations with a pan-Arabism orientation. Founded in Paris in1911, it played a key role in setting the political program for Arab independence when its supporters met with Prince Faisal bin Al Hussein and agreed to establish an independent Arab state In Iraq and the Hijaz. They suggested an Arabic flag of four colors inspired by a verse of poetry from Safi Al Din Al Hilli: “White are our acts, black our battles, green our fields, and red our swords”

The Sykes-Picot agreement came as the first stab in the nascent Arab project. It divided the country after it fell victim to the manipulation of the major powers and Arab nationalism had not yet built a clear ideology. Tthis was not achieved until the appearance of Sati' al-Husri, who can be considered the first theorist of Arab nationalism in the form that political parties and currents later adopted. Through his efforts, nationalism moved from a political tendency to a secular modernist thought based on the connection of language, history, and land away from religious affiliation.

Al-Husri, through the positions he held as Iraq’s Education minister and then director of General, was keen to spread nationalism in the ranks of authority. Unfortunately, his ideas were taken out of context and transformed into what Uday Al-Hawari described in his book, "Radical Arab Nationalism and Political Islam", as “a simplistic political philosophy reducible to a moral Manichaeism that knows nothing of the cultural foundations of modernity or the sociological complexity of Arab societies and their contradictions.”

The Syrian professor of philosophy Zaki Al-Arsuzi was influenced by al-Husri's ideas and employed nationalist ideology in calling for the establishment of a party that “resurrects the Arab nation to lead its message to the world.” Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar took over the task, and the Ba'ath Party was established in Syria in 1947 and Iraq in 1953. The arrival of these two organizations represented the beginning of Arab nationalism being stripped away from the rosy goals of achieving unity, the utopian slogan of nationalists.

The most obvious form of the crisis appeared in Egypt when the Free Officers Organization adopted an extremist nationalism, which Gamal Abdel Nasser relied on to launch his own project in an Arab cover, making the Arab people support him for the dreams of modernization and unity, and liberating Palestine. Far too many Arab leaders use the latteras an excuse for their disastrous mistakes, suppression of public opinion, and repeated economic failures. In fact, the corruption of their governments and the wasting of their country’s resources under the pretext of arming in the face of the “enemy” continues while ignoring the deteriorating conditions under which their people struggle.

The nationalist orientation that the regimes in Algeria, Libya (Muammar Gaddafi), or Sudan (Jaafar al-Nimeiri) knew was not better; they were all regimes that rode the wave or exploited it later except for their individual interests.

The nationalist parties did not achieve any of the Arab nationalism slogans. Rather, access to power or staying in it became the ultimate goal and highest ambition. The project of the Arab renaissance fell resoundingly, causing many Arabs to retreat into the vortex of non-national ties, such as clans, tribes, and sects, after they failed to achieve the unity they aspired to and found themselves living in failed states whose political parties are, at best, a reflection of rampant power grabs, tyranny, stagnation, and inter-conflicts.

Thus, the banner of so-called nationalism under a repressive Arab regime turned into a scarecrow full of straw and emptied of its human content and meaning. It became the enemy of freedom and peace, a weapon in the hands of regimes that could not offer their people anything but slogans and endless promises.

Parties and movements that adopted the Arabism ideology failed miserably to create a nationalism of a human nature synonymous with freedom similar to its French counterpart, emphasizing individual rights and giving human society a priority over all divisions. Arab nationalism has turned into a repugnant discourse that its political parties do not tire of repeating to their supporters as they set the slogan of complete unity among Arab countries as a condition for building their countries and moving them to the path of improvement and development.

In fairness, we have to admit that our failures as Arabs are not the product of the nationalism that unites us. Nationalism, even for Benedict, is essentially a positive imagination that shapes belonging and builds meaning, and it has been associated with the idea of the modern state in the West, which linked civilization with patriotism-nationalism. It is a spiritual-cultural bond based on language, culture, history, and common destiny before being a political bond that presupposes the convergence of the Arab peoples under a single rule or political system. Moreover, It does not end or negate if this difficult condition is not met, but it can be a mold in which all the ingredients are fused into a mixture that does not eliminate each other.

Arab's nationalism bore, without guilt on its part, the blame for the mistakes of the Arab parties and leaderships to which it belonged. The images of these people remained bright, while this human bond was distorted and even subjected to blasphemy when some tried to show it as contradicting Islam. Hostility to Arab nationalism, or showing it as a devil that causes all our misfortunes, is nothing but an attempt to escape from responsibility — an escape that we need to stop.

We must clearly distinguish between nationalism as an idea or theory and the ideological nationalism that appeared in the behavior and policies of parties and movements that, after the independence of their countries, took over the reins of power through coups. These ideologies never believed in liberalism or the establishment of civil society, but enabled regimes to practice dictatorship with the blessing and silence of dreamy peoples-.

After their independence, it seems that most of our Arab countries experienced regimes that carried an innate tendency to adapt all concepts to serve their narrow interests, turning our noble causes into a vehicle for them to monopolize power for many years. However, does this mean that we are no longer able to redirect the compass and remove the impurities that cover the beautiful face of our nationalism?

It requires courage and bravery in renewal and a common determination to break the narrower loyalties, given that nationalism, in general, constitutes the meaning of modern man. Our nationalism, as Arabs, includes components that were not available to other successful and fruitful nationalities through which we can generate new forces to be added to our efforts to build our countries separately. Our Arabism is an essential part of our existence and a cornerstone of our identity that we would never give up.

But we want it to be a comprehensive nationalism based on the free choice of a conscious and responsible human being, separated from all forms of populism, isolationism, and exclusion, and aimed at building peace in our region and moving it forward to prosperity and modernity.

Keep in touch

In-depth analyses delivered weekly.

Related Analyses:

.jpg)